The economic flaw at the heart of public education.

The View from the Strip Mall Office.

Sometime during my senior year in high school, I found myself in need of a signature from Dr. Thomas Hasenpflug. Dr. Hasenpflug was the long time superintendent of my school district. I don’t recall the exact circumstances, but it probably had something to do with my entering college—at Auburn, in Alabama—before I had officially graduated from high school. Or something. I don’t remember.

I found my way to his office, which was tucked into a nondescript strip mall in a nondescript part of town, and discovered that Dr. Hasenpflug ran the entire school district from that modest space, assisted by a business manager—whose name escapes me—and six staff members. All the staff were women, at least on that particular day, and I remember being both impressed and, perhaps, a little scandalized that the two men had six secretaries between them. Of course, they weren’t all secretaries—though that’s what my teenage brain, steeped in the casual sexism of the time, assumed. In retrospect, there was probably a bookkeeper or two, maybe an accountant, and certainly someone managing payroll and personnel records. This was before computers, remember—every form, every ledger entry, and every report had to be typed, filed, and tracked by hand.

A Half Century of Rising Costs and Falling Outcomes

I’ve been thinking about my school days of late because President Trump recently signed an executive order attempting to shut down the U.S. Department of Education. That Department was created in 1979, during the administration of President Jimmy Carter.

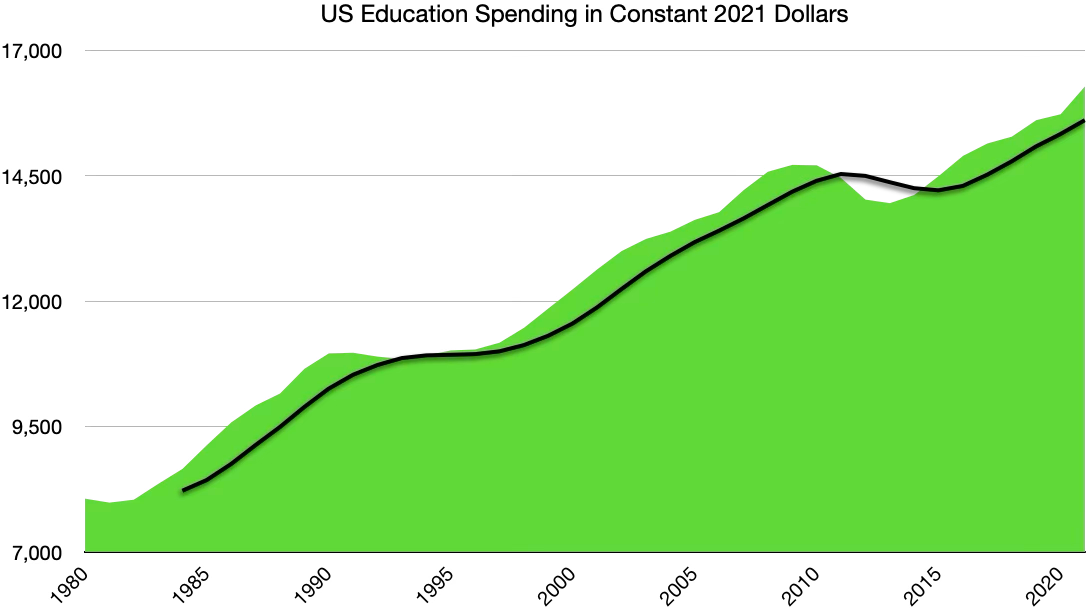

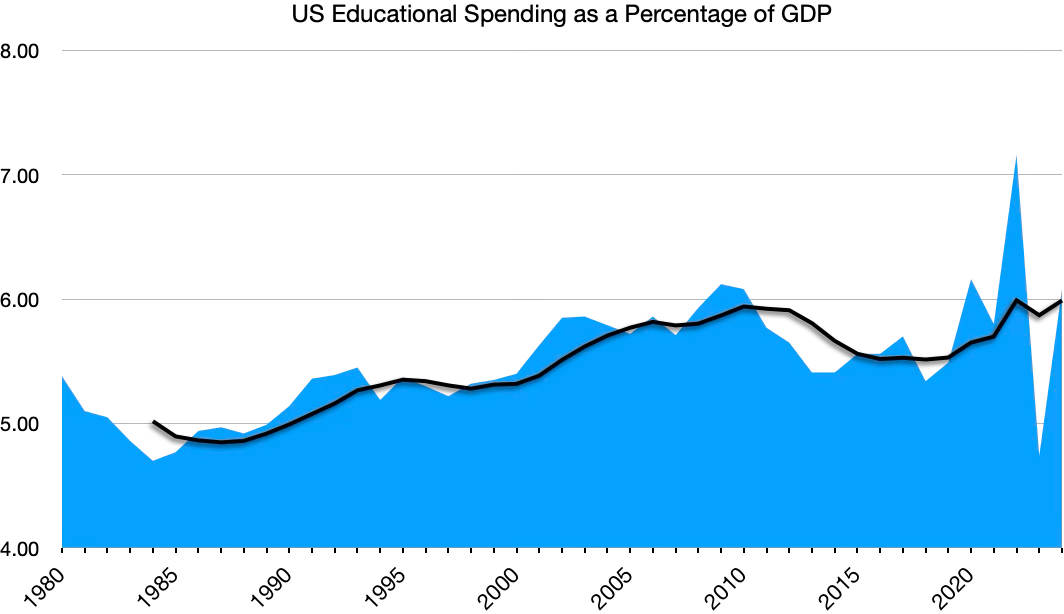

I can’t say I was surprised to learn that since the Department’s founding, education spending in the United States has increased—on an inflation-adjusted basis—by over 250%. During that same period, spending, as a function of Gross Domestic Product has risen from about 5% to over 6%. These are massive increases, and President Trump has reasonably called into question whether parents, students, and taxpayers are getting good value for their money.

Because while spending has gone up, educational outcomes have trended in the opposite direction.

In 1973, when I graduated, the United States was the unquestioned global leader in educational achievement. Test scores in reading and math were either the highest or among the top two or three in the world.

Since then, the bottom has dropped out. Today, the U.S. ranks a dismal 31st—behind Hungary, and just ahead of Taiwan and Greece.

Hungary, for the record, spends far less on education than the U.S.. The United States spends approximately $20,000 per pupil per year. In Hungary the number is less than $10,000. The US devotes over 6% of GDP to education. Hungary, about 4.5%.

Hungarian teachers make around $32,000 per year. In the U.S., twice that.

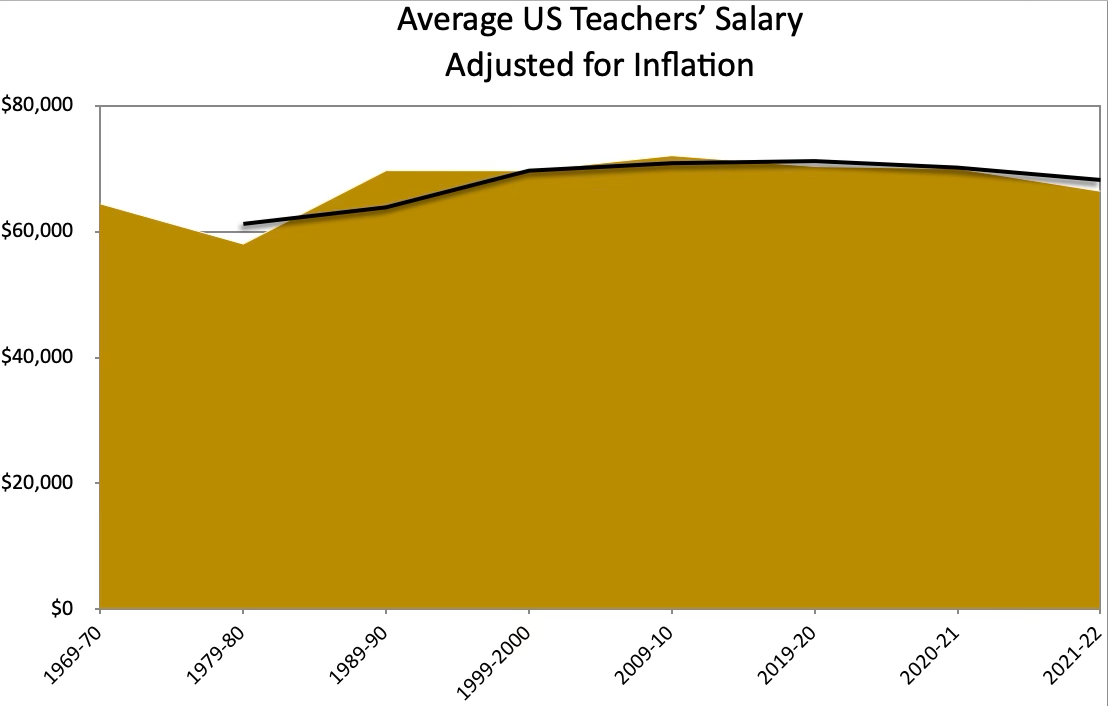

The massive, 250% increase in inflation-adjusted education spending over the past 45 years got me thinking: teachers must be making bank now, right?

As it turns out—not so much. I was genuinely shocked by the numbers.

Where the Money Didn’t Go

Back in 1970, U.S. teachers earned an average of $64,400 per year (in today’s dollars). Today, that number is $66,400. That’s a $2,000 raise over more than fifty years, despite a spending surge that would suggest a much different story.

Given the trend in educational outcomes, one could argue that teachers are overpaid. But to me, the more likely explanation is this: paltry salaries are driving away the best and brightest from ever entering the profession in the first place.

Which raises the obvious question: If the money isn’t going to teachers, where the hell is it going?

The numbers aren’t easy to pin down. But in the fifty-some years since I graduated high school—when Dr. Hasenpflug, a business manager, and six staffers ran the entire district out of a storefront—a few things are clear:

- In the school district in which I grew up, total enrollment has fallen by over 2,000 students, down to around 7,500. This is the case in most of the country.

- The district has closed two schools, including my own elementary school. Likewise, hundreds of schools close in the U.S. every year.

- That same elementary school, built in the early 1960s, was closed in 2010 and converted into the district’s headquarters.

- Today, that staff of eight has given way to a sprawling bureaucracy. The same district that once ran out of a modest strip mall store front now employs over 120 administrators.

- 120 administrators. For a district that is 20% smaller.

And there’s your problem.

From Educator to Functionary

In the mid-nineties, I was teaching continuing education classes in financial planning at a local high school. I was assigned to a classroom that belonged to a young English teacher. I remember this vividly because she was teaching one of my favorite novels—Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead.

One evening, as I was setting up, we got to talking. She struck me as bright and capable—but also thoroughly disillusioned. Angry even. With little prompting, she told me she was ready to quit the minute her student loans—covered by the district as part of her contract—were paid off.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because I don’t get to teach. I regurgitate. They tell me what to say, then sit in the back of my classroom to make sure I say it. No one cares about learning. We teach to the test. And it’s getting worse.”

She also mentioned the lack of discipline, social promotions, and the constant pressure to make sure everyone got a good grade.

It struck me as such a shame. She seemed like someone who wanted to inspire young minds—and probably could have, given half a chance. And she was teaching The Fountainhead, which she told me had been a huge fight just to get on the syllabus. “And it wasn’t worth it!” She said in obvious disgust.

She was disgusted because it is disgusting.

The Bureaucracy That Ate a Profession

Here was a young, intelligent, intellectually ambitious teacher—under the thumb of an administrator, who was under the thumb of another administrator, who answered to another, and so on, until someone was ultimately under the thumb of the U.S. Department of Education.

And as someone who spent a little time teaching adult education classes—hardly a credential, I admit—I came away with a powerful sense of how real teaching works. Teaching and learning describe a relationship—a dynamic, responsive, human connection between a teacher and a student. It’s not about checking boxes on a lesson plan. It is most definitely not about practice exams.

It’s about the look in a student’s eyes, the questions they ask, and the questions they ask about the answers they’re given. It's about the magical moment when a student nods in recognition—when they get it. And that moment—that magic—matters more than all the government studies in the world.

Some teachers are good. Some are great. Some are dreadful. But even the worst of them is better than the most brilliant administrator—because that teacher is in the classroom. They’re asking and answering questions, reviewing homework, grading papers. In my view, those daily, imperfect interactions are the educational process.

And if the English teacher who lent me her classroom—and fought to teach The Fountainhead—is to be believed, we’ve thrown all that away.

This slow suffocation of real teaching has a name: the U.S. Department of Education.

A History of Expensive Failures

Consider the following list:

- A Nation at Risk (1983 – Reagan administration)

- Goals 2000: Educate America Act (1994 – Clinton)

- No Child Left Behind (2002 – George W. Bush)

- Race to the Top (2009 – Obama)

- Every Student Succeeds Act (2015 – Obama, signed with bipartisan support)

These programs all had several things in common. Each spent billions upon billions of dollars. Each enlarged and entrenched the control of the bureaucratic and administrative class—at the expense of teachers. And each failed to bend the curve, even a little bit, on student academic achievement.

Each was a comical failure.

And now we have President Trump, who wants to shut the whole thing down.

I vividly remember the debate in the late 1970s over the Department of Education Organization Act—the legislation passed by Congress in October 1979 that officially established the Department. In general, I’m deeply suspicious of government initiatives like this. In my view, they’re always too expensive, they empower bureaucracy, and they stifle innovation.

That said, I was also hopeful. At about that time, I had studied ERISA—the federal pension reform law passed in 1974—and, young and impressionable though I was, I found it thoughtful, well-designed, and ultimately beneficial. That left me cautiously optimistic that maybe, just maybe, education reform could follow a similar path.

As is so often the case, I was wrong.

Public schools in the U.S. are typically funded through local property taxes. But some towns—especially those with large populations of poor and minority students—simply didn’t have the tax base to adequately fund their schools. The idea was that federal involvement could equalize budgets and, over time, equalize outcomes. Even now, I find that argument persuasive.

It was also argued that a federal education establishment would serve teachers. It would elevate the profession in the eyes of the public and among young people considering their career options. And help raise teacher salaries.

If that was the lesson plan, the Department of Education gets an F-minus. I see beauty school in its future. Maybe Frenchy can show it how the scissors work.

As we've already discussed, teacher salaries have gone precisely nowhere in the last fifty years. And everywhere you look, teachers are embattled. Sometimes because of nonessential curriculum—whatever the latest politically correct nonsense happens to be—crowding out reading, writing, and arithmetic. Sometimes because of the militant postures adopted by teachers' unions, especially around reopening schools during the pandemic.

From where I sit, the teaching profession is at a low ebb. Perhaps its lowest.

And what are we to make of the progress promised to our most vulnerable students—those in low-income and minority communities?

Back in the 1970s, the scandal du jour was that majority-Black high schools were graduating students at rates below 50%. Majority-white schools were at 80 or 85%. The problem, we were assured, was money. Money would solve everything.

Today, many majority-Black schools have attendance rates below 50%. Forget graduating—kids aren’t even showing up. And yet the answer, as always, is more money. More funding. More programs. More academic studies, each one proving that the solution is more money.

In fact, much of the overall decline in academic performance over the last fifty years can be traced to the particularly poor outcomes in low-income and minority communities. White students, by and large, are going to school, graduating, entering college, even earning advanced degrees in engineering, science, and math. And for the most part, they’re succeeding.

But the very people the Department of Education was created to help—its reason for being—have continued to fall further and further behind.

Perhaps it was a worthwhile experiment. But it has failed. And we would be wise to be done with it.

In this regard, I find myself in agreement with President Trump. As usual, however, he proceeds in precisely the wrong way and—missing the opportunity with which he’s been presented—with the wrong objectives.

As anyone who's ever had a Schoolhouse Rock ear-worm can tell you, presidents cannot, on their own authority, overturn an act of Congress—like the Department of Education Organization Act. Whatever “reforms” this president enacts by fiat can and will be undone by the next Democratic administration.

Worse, Trump’s egregious norms violations here could hand his political adversaries a blueprint. When they return to power, they’ll use the same tactics to expand—not limit—the reach of the Department of Education. And probably other agencies Trump would object to as well.

Climate emergency, anyone? Abortion? Let’s cut the defense budget!

Trump has proclaimed that he won a landslide victory last November. He says he has “a beautiful mandate.” He’s also spent the last forty years telling anyone who would listen that he is, in his words, a paradigmatic dealmaker.

A Better Deal, Left on the Table

So here’s a thought, President Trump: make a goddamn damn deal.

If you genuinely believe that government needs to shrink—and that the education establishment is overdue for reform—then make a deal—pass some legislation.

If my young English teacher friend is any indication, teachers—or some teachers, anyway—agree: education needs to be reformed. The Department of Education’s annual budget swelled to over a quarter of a trillion dollars during the Biden years. Want to cut that? Perhaps offer to share some of the savings with teachers in return for their support. You know, a deal.

Surely there are Democrats—especially in swing districts or states—who might see it in their political self-interest to join such a coalition. I think there are at least sixty Senators, maybe more, who might hold their noses and vote to shut down a failing institution in exchange for a five percent increase in teacher pay—especially if states were required to match it.

Imagine the political victory Trump could claim if he went on TV, cited the dismal history of teacher pay over the last half century, blamed it on the Department of Education, and announced that all teachers would immediately get a ten percent raise.

Imagine what might happen to his poll numbers.

But this will never happen with Trump’s approach.

Right now, his adversaries are whispering the obvious: He won’t be around forever. Let’s wait him out. Let him self-destruct. Stay unified, and when we’re back in power, everything will go back to normal.

If Trump proposed actual legislation—and worked to bring disparate factions on board—that dynamic would change. Instead of mindless opposition, we might see negotiation. Buy-in. Progress. Genuine lasting reform.

Trump's Goals Are Too Modest

But my objection to Trump’s plan neither begins nor ends with his tactics as wrong headed as they may be. It’s his objective I find most troubling. Like much of the Republican Party in recent decades, Trump is crystal clear about what he opposes. What does he support? Not so much.

President Trump is missing a tremendous opportunity. Right now, he has a chance to remake American education—and, in the process, rally millions of low-income and minority voters who have traditionally supported Democrats to his movement.

Don’t just squash the Department of Education, no matter how justified. Use this moment to turn the country toward education freedom. Toward school choice.

The word monopoly has been so misused it’s almost lost its meaning. But most people still instinctively know what it is: a market with just one seller. True monopolies are rare in a free market—because if a company tries to earn excess profits, it invites competition. That’s how markets work.

Still, in theory and in practice, monopolists often don’t compete by improving their products or services. Instead, they fight to preserve their market power. And all too often, that fight involves government protection—regulation, licensing, or other policies that shield them from challengers at the expense of consumers.

Which brings us to coercive monopolies—those whose dominance isn’t just economic, but legal. Think public utilities: power, water, maybe garbage collection. They’re given freedom from competition by law, but in return, they usually surrender the freedom to set their own prices.

Now, before we get back to public schools, let’s talk about another type: the bilateral monopoly. This is a market with not just one seller—but also one buyer.

Picture a small town with one large factory. Everyone works there. But all the workers are represented by a single labor union. The factory knows the union has no alternatives. The union knows the factory has no alternatives. Neither side can dictate terms, because both sides hold all the power on their end. Prices aren't set by competition—they’re set by negotiation. It’s a market defined not by prices, but by power.

The automobile industry, for much of its history, was a textbook example of this. And we’ve seen how that has turned out.

Of course, reality still intrudes. The factory must sell its products to customers who do have choices. And union members can quit, move, or rebel. That real-world pressure limits the worst excesses.

But now imagine a market where there’s one buyer, one seller—and they’re the same entity.

That’s public education.

The Sovereign Bilateral Monopoly

Public education, in my view, is a unique kind of bilateral monopoly—one immune even to the pressures of reality.

Using its taxing power, the government raises money—mostly with impunity—to fund a monopolistic service. Then, using its police power, it forces people to buy that service while largely excluding competition.

Want to send your kids to a private school? Excellent. But you still forfeit your tax dollars. Your public school stinks? Too bad. Maybe vote us more money.

I call this system a Sovereign Bilateral Monopoly—a market in which the buyer and seller are one and the same, and whose power is enforced not by consumer choice, but by the state. Not by competition but at the point of a gun.

And what are the results of such a system?

Look at American education since 1980. And please—don’t tell me teachers have a seat at this table. Just look at teacher pay over the last half-century.

President Trump, in my opinion, is uniquely positioned to break this system apart. Because it is a system where everybody loses—and must lose.

Except, of course, the 110 administrators now working in my old elementary school, and their handmaidens in the IRS and the Department of Revenue.

Trump says he wants to abolish the Department of Education by handing its power to the states. But how would that change anything? It wouldn’t break up the Sovereign Bilateral Monopoly. It would merely redraw its lines.

Real reform, in this instance, means breaking the table into millions of pieces, not rearranging the chairs.

The Power to, the Power to Teach, and to Learn

No real change will come until the only two parties that matter—parents and teachers—are the ones with power. Give it to them. Give it to them, President Trump! Not to governors, or state boards or federal agencies or partisan commissions. Just parents and teachers.

Do that, and watch costs collapse. Watch choices explode. Watch American education, once again, lead the world.

Trump has a rare opportunity. But it won’t be realized through a press conference or an executive order.

It will require courage. Not to 'own the libs.' Not to 'dismantle the administrative state.' Just to do the obvious thing no one else will do: Make a deal and give the power to the people who actually care about the kids.